When we think of World War I heroes, we often picture soldiers in muddy trenches, medics rushing into no man’s land, and nurses tending to the wounded.

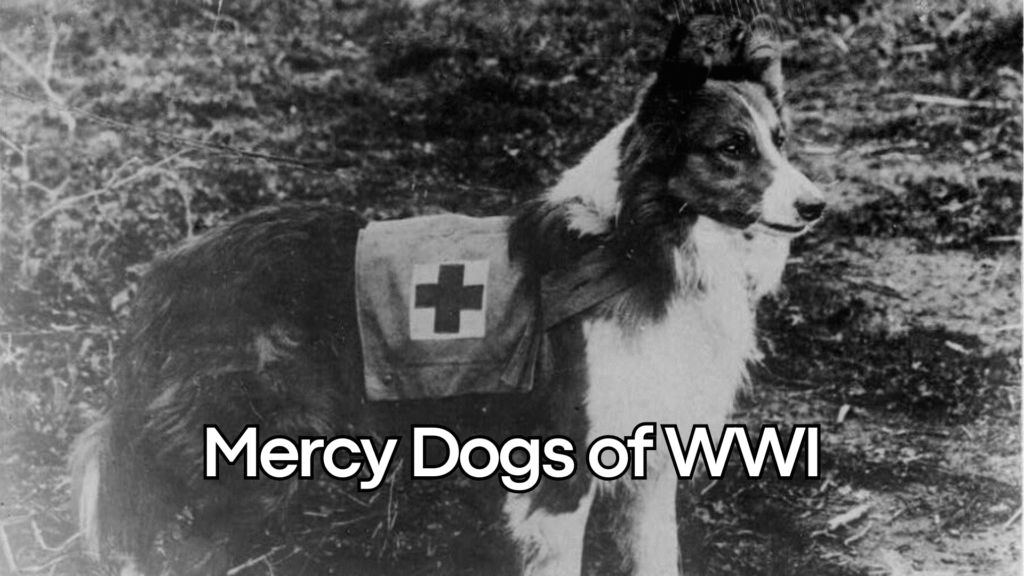

But among them were other, quieter heroes, four-legged rescuers known as mercy dogs.

These dogs worked without fanfare, often under fire, risking their lives to find and comfort the wounded. They weren’t just animals in uniform; they were lifelines for soldiers facing the unthinkable.

Hello and welcome to Dog Works Radio. I am your host, Michele Forto, and the lead trainer of Alaska Dog Works, where we help you have the best relationship possible with your dog. We have been spending a lot of time lately researching articles about service and therapy dog history as we re-launch our programs to serve our clients better, and we knew we wanted to tell the story of the Mercy Dogs. The mercy dogs of World War I were more than battlefield tools; they were comrades. They brought hope to the hopeless, eased the fear of the dying, and gave soldiers a reason to believe they might make it home.

Their bravery, devotion, and service deserve to be remembered alongside the human heroes of the Great War.

How the Mercy Dog Program Began

The idea of using dogs for battlefield rescue took shape in Germany in the late 19th century. Jean Bungartz, a German painter and animal advocate, founded the first organized medical dog program, known as the Sanitätshund corps.

By the time the First World War erupted in 1914, Germany had thousands of trained dogs ready for service. France, Italy, and Austria had similar programs. Britain was slower to act, it wasn’t until 1917, after heavy losses on the Western Front, that the British War Dog School was formed under Major Edwin Hautenville Richardson.

Richardson had long believed in the value of military dogs. He was proven right, by war’s end, these animals had saved countless lives.

What Mercy Dogs Did on the Battlefield

Mercy dogs were trained to do something no human could do as efficiently, search vast, dangerous battlefields quickly and silently.

After an attack, they were sent into no‑man’s‑land at night or during lulls in fighting. Each carried saddlebags stocked with bandages, water, and sometimes small flasks of brandy or rum.

When they found a wounded soldier, they had two main jobs:

- Stay with the soldier, providing comfort and warmth until help arrived.

- Or, if the soldier could not move, return to their handler with an item of the soldier’s clothing as a signal for medics to follow.

Mercy dogs were trained to ignore the dead and focus only on those who could still be saved, a grim but necessary skill. In some cases, they even dragged soldiers to safety or guided stretcher‑bearers through the chaos.

The work was perilous. Poison gas, artillery fire, and sniper rounds claimed many canine lives. Yet they continued to serve, seemingly aware of the urgency of their mission.

Breeds That Served

While any capable working dog could be trained for the role, certain breeds proved especially effective:

- Boxers — Strong, loyal, and fearless, Boxers were prized for their devotion to their handlers and ability to comfort the wounded.

- German Shepherds — Intelligent, trainable, and steady under pressure.

- Doberman Pinschers — Agile and alert, they excelled at navigating rugged terrain.

Smaller mixed-breed dogs also served, especially as message carriers, but the physically demanding rescue work often required larger, more robust breeds.

Individual Stories of Bravery

Numbers and facts only tell part of the story. The real measure of the mercy dogs’ courage comes from the lives they touched.

Sergeant Stubby

Probably the most famous American war dog, Stubby was a Boston‑Terrier-type stray who served with the U.S. 102nd Infantry Regiment. He warned troops of mustard gas attacks, located wounded soldiers, and even captured a German soldier trying to map Allied trenches. He participated in 17 battles, earning two Purple Hearts and a place in history.

Rags

A scrappy mixed-breed terrier found in Paris, Rags became a messenger dog for the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. During the Meuse‑Argonne Offensive, he carried critical messages through heavy shellfire, saving lives by keeping communications open. Injured and gassed, Rags survived the war and became a beloved mascot back home.

Caesar, the ANZAC Dog

Serving with the New Zealand Rifle Brigade, Caesar, a bulldog, was trained to locate wounded soldiers and lead medics to them. Wearing a gas mask when needed, Caesar rescued numerous men before being killed in action. His unit deeply felt his loss.

Philly

Smuggled to France by the men of the U.S. 315th Infantry Regiment, Philly was a mixed-breed female who proved her worth on the front lines. Wounded and gassed herself, she still managed to alert troops to surprise attacks. The Germans placed a bounty on her head, a testament to her effectiveness.

The Scale of Their Service

It’s estimated that 10,000 mercy dogs served on the Allied side during World War I, saving thousands of lives. Germany alone trained more than 6,000 medical dogs and employed over 30,000 dogs in various military roles. Many never returned home.

These dogs were not spared the dangers of war. Around 7,000 German war dogs were killed in action, with similar losses among the Allies. Yet their presence on the battlefield offered a rare combination of practical aid and emotional comfort.

Lasting Legacy

The success of the mercy dog program influenced the creation of later military working dog units in World War II, Korea, and beyond. Their ability to search for the wounded under fire also inspired civilian search‑and‑rescue programs, and, indirectly, the modern therapy dog movement.

Today, therapy and service dogs carry forward the same qualities that made mercy dogs invaluable: loyalty, intelligence, and an unshakable bond with the humans they help.

The mercy dogs of World War I were more than battlefield tools, they were comrades. They brought hope to the hopeless, eased the fear of the dying, and gave soldiers a reason to believe they might make it home.

Their bravery, devotion, and service deserve to be remembered alongside the human heroes of the Great War.

That’s it! What questions do you have for us? Please let us know on our social media, and we will do our best to address them in an upcoming episode.

Before we end the show, let’s press pause for a sec…maybe ask yourself, why did this resonate with me? What aspect of my relationship with my K9 buddy could I apply this to? And what am I going to do differently this week to make my dog’s training a little easier? So, take time to mull it over, talk it out with a family member or trusted friend, put some ideas down in your training journal, and then check back next week for our next episode.

And as always, I look forward to hearing your thoughts on this episode. So, reach out and find me on Instagram at akdogworks, and let’s spark a conversation. Until then, keep going! You are doing great! It is time to create the relationship with your dog that you always dreamed of.

Thanks for listening to Dog Works Radio. Find the show notes for this episode and all others at Alaska dog works (dot)com. Know someone in your life who needs help with their dog’s training? Be a hero and share our podcast with them, and we will see you next time.

Why trust us

At Dog Works Radio, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by a team with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts.

For this piece on the history of mercy dogs in World War I, Michele Forto tapped her experience as a longtime dog trainer, podcaster, and dog owner. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions, and our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing, and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and current. Read more about our team, our contributors, and our editorial policies on our website, Alaska Dog Works.com